Dear friends of Daily Philosophy,

Yesterday was International Women’s Day, and I thought that we might want to celebrate that a bit by having a look at the influence of women on philosophy over the ages and across cultures (at least a little bit). As I researched it, the article kept growing, so now we’ll have a two-part piece. The first part, the one you are reading now, will mainly deal with ancient and non-European women thinkers. The next part, coming next week, will go into women’s philosophy in the modern Western tradition.

In a bit of further news, Tomorrow’s Teaching, my newsletter about technology in education, now has 25 subscribers, which is great! It does not sound like much, but it took us only a week to get there. Tomorrow (Sunday) you will find a new article at TT, “Brainstorm Your Course With AI. From idea to syllabus in 20 minutes.” If you are interested in that and not yet subscribed, you can subscribe for free right here:

Women philosophers

It’s not easy to even find reliable information about women philosophers of past times. There are a handful here and there, but they are often centuries apart, while one could most likely name at least one male thinker who was alive at any random year since the time of Diotima. This, of course, is due to the fact that in most past societies women were not educated as well as men, did not have access to universities or other intellectual career paths, and, even when they could express themselves, were seldom taken seriously by their male-dominated surroundings.

With International Women’s Day just behind us, let us now have a look at some women thinkers of the past and from different cultures.

Gargi Vachaknavi (7th century BCE)

Gargi Vachaknavi was an Indian philosopher and debater of the Vedic period who appeared in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣhad.

When the king King Janaka of the Kingdom of Videha held a particular ritual ceremony, he invited all the learned sages of India to participate. The ceremony lasted for many days, and the streets were filled with scholars, holy men and the aroma of sandalwood and other offerings. The king wanted to have a contest to decide who was the greatest scholar, and he offered a prize of cows and gold for the scholar who would show the deepest knowledge of spiritual matters. The famous sage Yajnavalkya, convinced that he was the most accomplished wise man at the gathering, claimed the cows for himself and started to arrange for them to be delivered to his house. Out of the hundreds of sages at the meeting, only eight protested and challenged him to a debate contest — and one of them was Gargi, the only woman among them. In the end, Gargi lost the argument (as perhaps it was unthinkable that a woman at that time would trump the most learned of men), but at least she came second and her name is forever now part of the Hindu classics.

Aspasia (~470—after 428 BCE)

We know almost nothing with certainty of the life of Aspasia of Miletus, a philosopher and rhetorician. She was the partner of statesman Pericles, who led Athens through its Golden Age and the Persian Wars, and she was well-known in Athenian society. But ancient society being what it was, she was often portrayed as a courtesan, and descriptions of her focused on her sexuality and her influence on her famous partner.

The most detailed biographical information we have of her comes from Plutarch (46-119 CE), who wrote about her nearly seven centuries after her death. She was from Miletus, and therefore a foreigner in Athens, and she might have been a sex worker before she met Pericles, with whom she might have been married — or not. After the death of Pericles from the plague, Aspasia seems to have marries Lysicles, another Athenian politician. Unfortunately, he too died a year later, and Aspasia’s tracks disappear in the shadows of history.

Aspasia was portrayed in philosophical dialogues already during her lifetime. In dialogues written by Plato, Xenophon, and Aeschines, Aspasia is portrayed as an educated women with skills in the art of rhetoric, or public speaking, which might have been just the skill to have as the wife of Pericles, a well-known speaker. Some have argued that the famous Diotima, the wise woman of Plato’s Symposium, to whom Socrates attributes his insights above love, might have been based on Aspasia. Like her, Diotima is said to be from outside Athens, and she is a teacher in the secrets of love, which might be an allusion to Aspasia’s past.

In one of the most famous of Pericles’ speeches, the funeral oration for the fallen of the Peloponnesian War, Aspasia’s husband is quoted as saying:

“The greatest glory for a woman is not to be spoken about at all, either for good or ill.”

One wonders what Aspasia would have thought as she heard her partner saying these words. Words that would outlive both of them and stay alive in humanity’s memory for all time, while her own achievements would soon be forgotten.

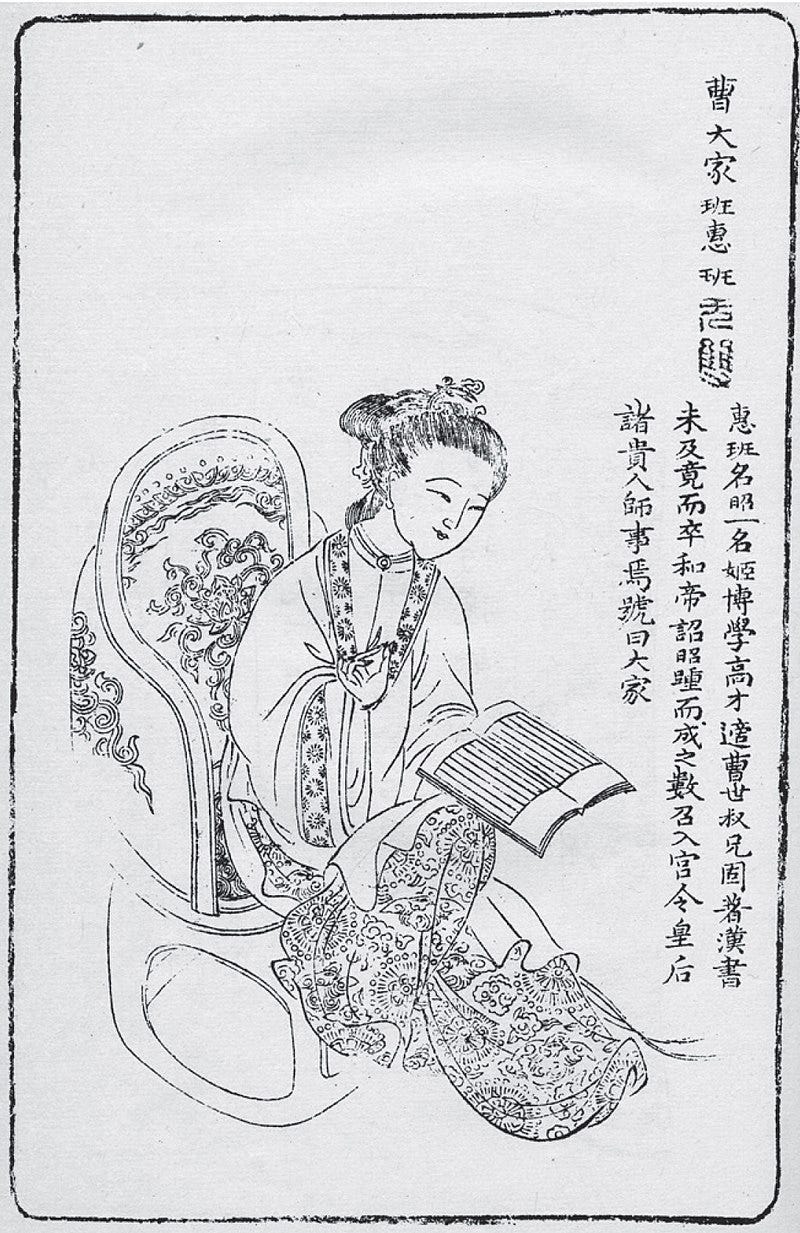

Ban Zhao (班昭, 45—120 CE)

Ban Zhao was a renowned Chinese philosopher, historian, and politician. She was one of the first female historians worldwide, along with Pamphila of Epidaurus. Among other works, she completed a history of the Han dynasty that her brother had begun, and she wrote Lessons for Women, a significant work that dealt with women’s education, moral obligations, and proper conduct, reflecting the cultural values of her time. She also seems to have been an instructor of Daoist sexual practices to the imperial family.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Daily Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.