In our history of ancient Greek philosophy, we’ve arrived at our first philosopher (although that title wouldn’t be claimed until later and by another thinker). Instead, Thales, our man of the week, is generally mentioned as the first scientist in the Western tradition. And Diogenes Laertius, our society reporter, also provided us with some amusing anecdotes about his life and works.

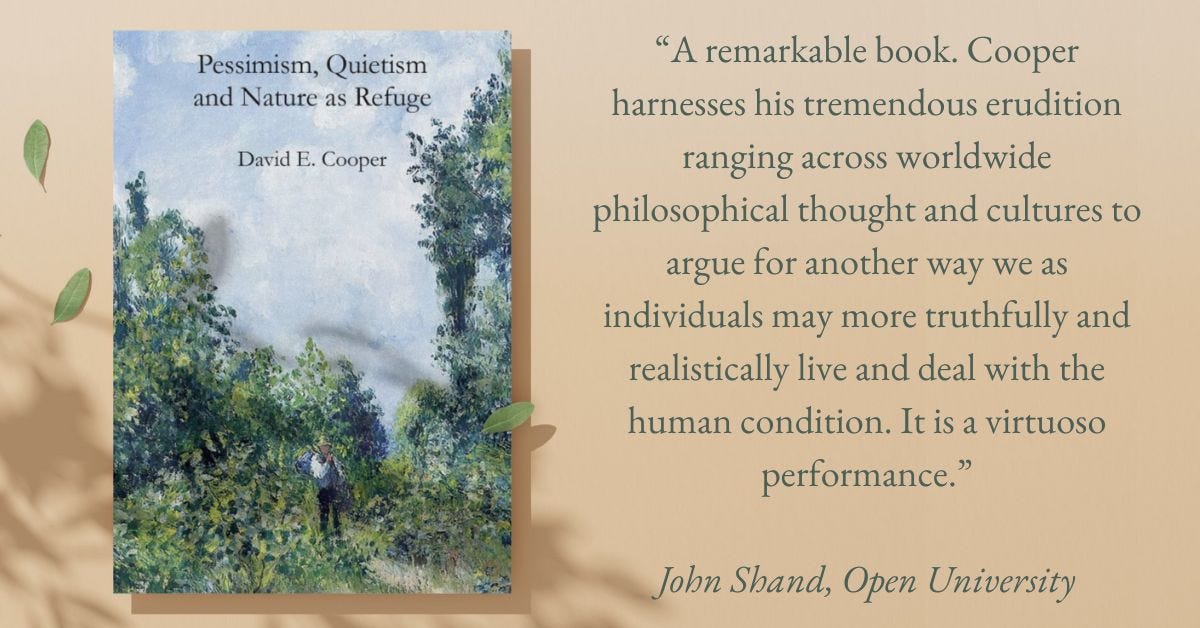

Before we begin, I am excited to briefly point you to a book from one of Daily Philosophy’s most committed authors and most generous supporters: David E. Cooper’s Pessimism, Quietism and Nature as Refuge is coming out on September 19th:

Prof Cooper has previously written about the topic on Daily Philosophy: The Rhetoric of Refuge. On the wish to retreat from the world.. If you are interested, you can find all of Prof Cooper’s articles right here:

https://daily-philosophy.com/authors/#DavidECooper

Finally, let me remind you of the deadline for our Daily Philosophy Global Essay Contest 2024, which is in two days, on September 1st, 2024, 23:59 GMT/UTC. There is still time to write something and take part! Find all the details here.

And now let’s jump back to ancient Miletus and the world according to Thales.

The first scientist

If you have heard anything about Presocratic philosophy, it will likely be that the first philosophers used to worry about what the universe was made of. They all had different ideas, and variously proclaimed that everything was made out of air, or water, or fire, or the infinite. We will get to know all of them throughout this series.

As opposed to many philosophers who became recognised only long after their death, Thales was famous already during his lifetime. For example, he is a regular in the lists of the seven Greek sages. These also varying over time, but our Diogenes Laertius names them as: Thales, Solon, Periander, Cleobulus, Chilon, Bias, Pittacus.

Diogenes, interestingly, names two first philosophers. He writes:

But philosophy, the pursuit of wisdom, has had a twofold origin; it started with Anaximander on the one hand, with Pythagoras on the other. The former was a pupil of Thales, Pythagoras was taught by Pherecydes. The one school was called Ionian, because Thales, a Milesian and therefore an Ionian, instructed Anaximander; the other school was called Italian from Pythagoras, who worked for the most part in Italy.

Thales was not the kind of philosopher who is only interested in arcane issues that no one else cares about. From the sayings attributed to him, he seems to be the kind of man who always has a clever and practical reply ready:

He held there was no difference between life and death. "Why then," said one, "do you not die?" "Because," said he, "there is no difference." ... To the adulterer who inquired if he should deny the charge upon oath he replied that perjury was no worse than adultery.

One day, somebody asked Thales (or so a story goes), if he was so clever, why wasn't he rich?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Daily Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.