Dear friends of Daily Philosophy,

Welcome back to your weekly dose of philosophy! In the past week, we had the first issue of the magazine in 2023 come out, both as a Kindle ebook and as a paperback. You can get both here on Amazon.

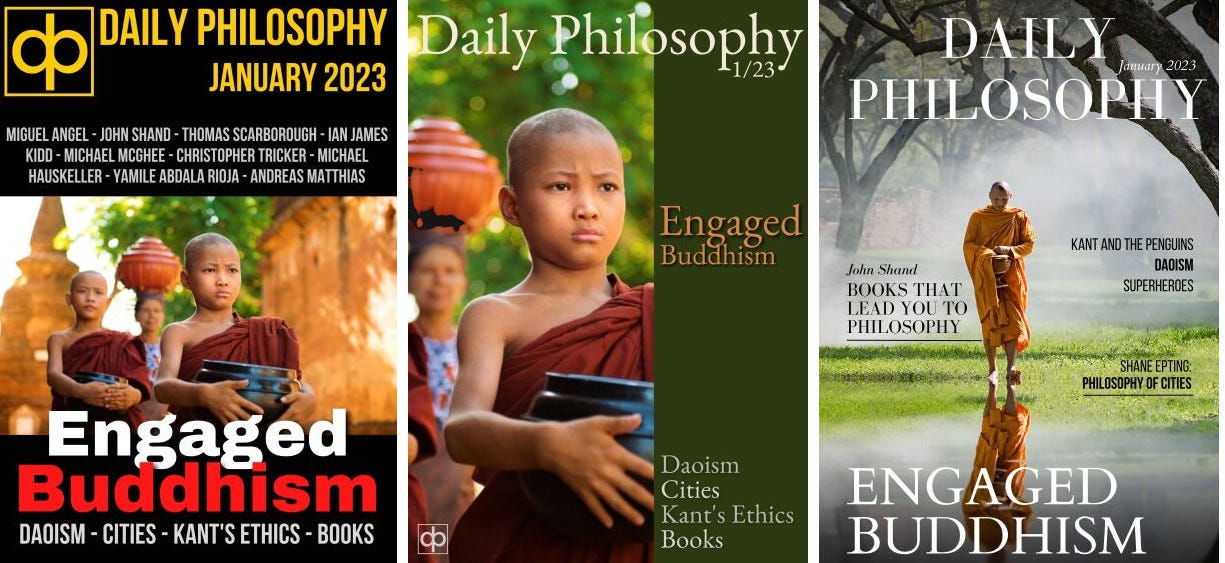

While preparing this magazine, even I could not fail to notice that the cover looked like it had been designed by a blind alien who had once read a definition of what the words “magazine cover” meant in human languages. So I spent a few days reading and watching videos on magazine cover design, and I tried to come up with something better. My second attempt was a green one that didn’t look quite as terrifying as the first, but it wasn’t particularly handsome either. With the help of advice from various friends and a template from Canva, I finally came up with the third, which is what you will now find on Amazon. In case you’re interested in such things, here is how the cover went through three iterations, from the first to the final one:

It’s still not perfect, of course, not even in my own eyes. For example, I didn’t find a way of putting the DP logo on it, and the words are much too small to make out when the cover is a thumbnail on Amazon. Despite their other obvious failings, at least the old covers were a bit more attention-grabbing. If you, dear reader, have any expertise in these matters and can suggest how to improve future covers, I’ll be very happy to hear from you!

I must also briefly throw in a mention here of a recent article in Wired by the brilliant John Danaher from Galway, who was so kind to write about an old article of mine. If you are interested in AI ethics, it’s well-written and interesting, like all of Danaher’s work:

The Case for Outsourcing Morality to AI.

That’s all my news for the moment. I’m working on a number of things, including new videos and the series on philosophy quotes, but nothing is yet ready to show. And my many classes this term mean that this newsletter is going to come to you on Saturdays, rather than Fridays, for the foreseeable future (this means until the end of April, at least).

Have a great February and enjoy your weekly article below!

— Andy

Should a Liberal State Ban the Burqa?

Brandon Robshaw (2020). Should a Liberal State Ban the Burqa? Reconciling Liberalism, Multiculturalism and European Politics. Bloomsbury Academic. 265 pages. ISBN (hardcover): 978-1-3501-2505-6. Get it here on Amazon. Hardcover: 120 USD, Kindle: 35.95 USD.

Is it morally right for liberal states to ban the wearing of Islamic dress that covers the face of the (female) wearer? And if so, for which precise reasons would such a ban be defensible?

The question is surely one that most of us have discussed with others at some point. When France banned the wearing of the burqa on French territory in 2010, a heated debate followed. Obviously, Muslims would be opposed to the ban — but even non-Muslims often rejected the measure and many of its possible justifications.

Things are not as easy as they may seem. The wearing of the Burqa (and its ban) touch on a number of pretty complicated philosophical problems.

For one, of course, there is the issue of gender equality and the freedom of Muslim women to wear whatever they like. Strangely perhaps for the Western observer, it turned out that many Muslim women reported that they would actually voluntarily choose to wear a Burqa. But if this is the case, then how can a state committed to individual freedom justify taking just this freedom away from Muslim women?

One could try to argue that the Muslim women who would like to go on wearing the Burqa might not have been entirely free in their choice. Perhaps they only accept the dress under the pressure of their culture, their religion, or other family members. And such pressure might even work subconsciously — the women affected might not even realise that they are not freely choosing and that they are instead the victims of a subtle ploy to restrict their freedoms, a ploy that included their early childhood education and the values that society and religion passed on to them.

But then, one might ask, is it the job of the state to solve such issues with a blanket ban on the wearing of this type of dress? Should the state assume the paternalistic stance of forcing women to expose their faces, even if they don’t want to, in the name of some “higher order” freedom? And if I want to cover my face for any reason, shouldn’t this be something that concerns only me?

Thinking through these problems leads to complex questions that require weighing superficial freedom of choice against perhaps a “deeper” freedom of choosing one’s values. Or weighing the preferences of those who genuinely want to cover their faces against the interests of a society who wants its citizens to socialise in the open. And the issues soon expand from there to cover all sorts of fascinating questions involving freedom, dignity, gender equality and what it means to live together in a modern, liberal society.

Style of the book

Throughout the book, the author Brandon Robshaw stays firmly with a liberal point of view. He already assumes, for example, that the Burqa-wearing will be voluntary rather than enforced:

Up until Chapter 11, I shall be assuming that the wearing of the burqa is voluntary. That is because I take it as a given that liberals would naturally be against coerced burqa-wearing. It is voluntary burqa-wearing that makes for the liberal dilemma.

This is refreshing to see, because all too often nowadays, someone on one side of an argument will use every rhetoric trick available to benefit their own position, including straw man arguments and ad-hominem attacks.

Not so this book. The one thing that I found surprising, almost astonishing, and, as I read on, increasingly delightful, is how honest, fair and balanced the treatment of the question is. Robshaw is a very careful, very systematic, very lucid thinker, and he does not seem to have any agenda except to clarify his question, debating as many arguments as possible from all sides. He treats every argument with the care and impartiality of a judge, but without the legalistic tediousness that one would expect from lawyers.

The answer to the question of the book’s title comes already on page two, and this again is a wonderfully refreshing change from the click-bait assaulting us all over modern media: “The astonishing truth about Burqa-wearing! Click here!” — This book, thankfully, is exactly the opposite: calm, lucid, thoughtful and clear. Robshaw:

The conclusion, which I am happy to disclose at this early stage, is that banning the burqa in a liberal state is unlikely to be justified. It could not be justified in terms of the welfare or autonomy of the individual who voluntarily wears it. It could only be justified on the grounds of harm to others. A ban might, for example, theoretically be justified if coerced wearing of the burqa were widespread. Such a ban would be regrettable, however, as it would override the free choice of those who wore it voluntarily. It would first be necessary to provide empirical evidence that such coercion was occurring; and any such ban could only be justified if there were no other, equally efficacious and better targeted means of preventing coercion. (p.2)

A short trip to the dark side

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Daily Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.